The bridge to Muk – Achille Jouberton

In the early morning of 25 June 2024, a supraglacial lake on Kyzylsu Glacier suddenly drained, unleashing large volumes of water through the proglacial stream, damaging bridges on its path, and cutting out the village of Muk from the rest of Tajikistan. Our annual visit to this area allowed us to reconstruct the timeline of this flood, as seen by different people and cameras along its path:

1 July – Our local contact Iskandar who lives in Jirgatol, one-hour drive from Muk, sent me via WhatsApp some photos and videos of a flood that destroyed the bridge connecting the village of Muk to the downstream region of the Muksu River on 25 June. My colleague Evan Miles looked at evidence of this flood event on Planet satellite images and identified that a lake on the surface of Kyzylsu glacier had disappeared between 13 and 25 June. The timing of the lake’s disappearance aligned very well with the flood and was most likely the cause of it.

22 August – We arrived at the base camp located in the vicinity of Kyzylsu glacier, at an elevation of 3364m a.s.l. This expedition was the annual visit to the Kyzylsu research site and took place within the framework of the PAMIR project. This was our sixth visit to this site since the beginning of its monitoring in June 2021, the main goals being to maintain the network of instruments and to retrieve the data stored locally since the last visit

23 August – We retrieved a full year’s worth of photos taken every 2 hours by a Canon E2000D camera powered by a solar panel and overlooking our pluviometer weather station and Kyzylsu glacier in the background. The photo taken at 5:40 am on 25 June clearly showed very high flow in the proglacial stream, which profoundly modified the stream bed.

25 August – We visited an alpine village located further down the stream at an elevation of 3200m a.s.l. and one-and-a-half-hour walk from our base camp. Since 2021, a hunting-style time-lapse camera overlooking the stream has been installed in this location as well as an air temperature station with a mast graduated with coloured tape to quantify the snow height during the winter months. To our surprise, the camera and temperature sensors were not there anymore when we reached their location, which the flood alone could not explain, as the tripod of the camera was profoundly secured in a cairn which didn’t seem to have moved.

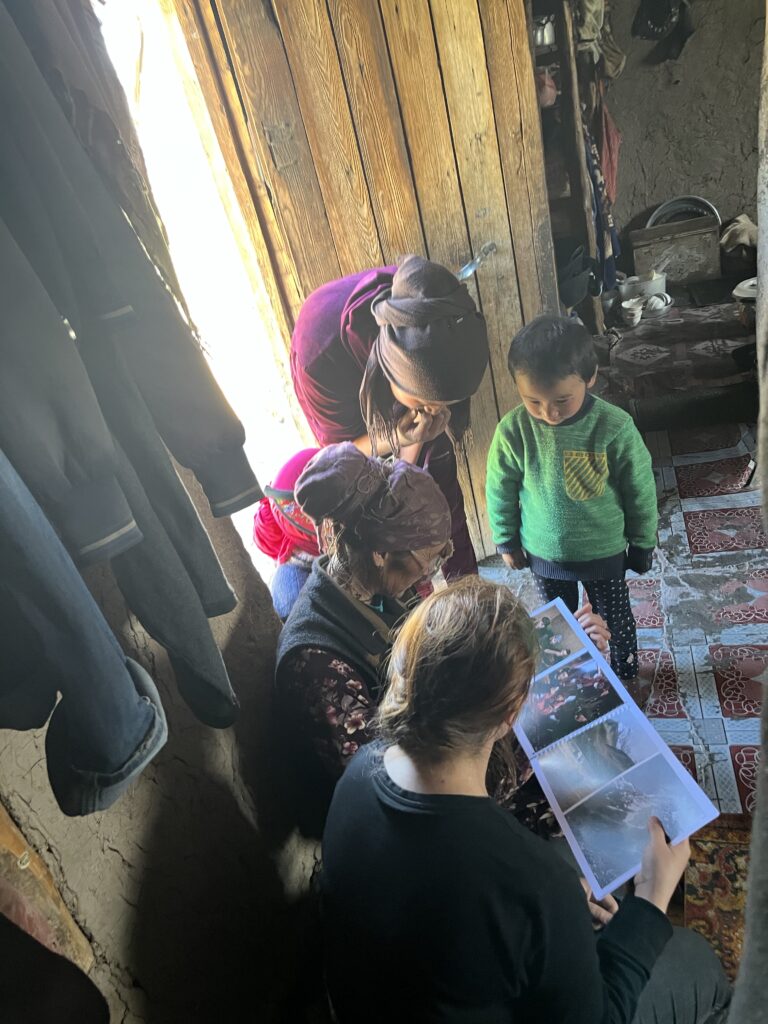

We then visited the shepherd’s house nearby, with whom we have built great affinity over the years despite the language barriers. The shepherd brought us the camera that he safely stored in his home, as well as the remaining air temperature structure stored on their roof, and told us his version of the story: At 4:00 am on 25 June, a loud noise woke him up, he went outside and quickly realised that a large flood was happening in the stream a hundred metres away from his house. His first reflex was to run, grab, and secure our time-lapse camera and temperature sensor. He managed to get the structure of the temperature sensor that was being carried away by the flood, although the temperature data logger was lost in the river. After further discussion with him, we understood that this flood and a similar but smaller one from June 2023 are the only known events of this kind for this stream in the past 30 years. We were very grateful for his initiative and for the meal his family graciously offered us shortly after our arrival. As a gesture of our appreciation, we presented them with a photo book featuring pictures taken by Jason Klimatsas in September 2023, and we promised to fulfill their request by bringing them a 50-metre climbing rope in 2025.

28 August – From our base camp we drove down to the outlet of the catchment we study. The bridge over the stream fed by Kyzylsu Glacier towards Muk is located there. In September 2023, we installed two hunting cameras to monitor snow depth and stream water level variations in this location. Fortunately, both cameras were still there upon our arrival, even though one was installed very close to the streambed, and we could retrieve full records of daily photos. I compiled a time-lapse from the photos:

In the video, we can see the bridge disappear, and the construction of a new – wooden – bridge, which does not allow cars to cross. Local villagers now cross it either on foot or on motorbikes and use a car pick-up/drop-off system on either side of the bridge. It is unclear if and when a full bridge will be rebuilt, especially considering that a similar bridge was already destroyed here in 2023 during another glacial lake outburst flood. To monitor the water level variation of the stream, we installed a Lidar device measuring the distance from the sensor to the surface of the water. We secured it on a large boulder overlooking the stream, which shouldn’t be affected by another flood, but only time will tell.

Glacier outburst floods, sudden releases of water from glaciers or glacial lakes, have recently gained attention in High Mountain Asia due to their increasing frequency and severity, driven by climate change and posing significant risks to downstream communities and infrastructure. To the west side of Kyzylsu Glacier, Baralmos Glacier hosts several supraglacial lakes that drain and cause floods downstream several times a year. The cause and mechanisms behind the occurrence of such events remain a topic of ongoing research, as well as the mitigation measures necessary to protect the local population and infrastructure. For this purpose, our expedition to Kyzylsu Glacier was jointly conducted with a team investigating Baralmos Glacier, as part of the UNESCO project GLOFCA focusing on glacier lake outburst floods.